When the moment comes to make an entrance, meet up in style or simply watch the world go by, Le Grand Hall at Badrutt’s Palace Hotel’s is the perfect venue. However, it did not just spring from the ground one day, fully formed and ready to be enjoyed. On the contrary, it is the result of a great deal of work, care and thought that stretch back to the late 19th century.

Connoisseurs of the arts may recognise that the architecture of the hotel’s elegant lobby takes inspiration from the Renaissance Revival. An aesthetic ethos that was enjoying great popularity at the time of the Palace’s construction between 1894 and 1896, it uses well-judged proportions and well-balanced symmetries to create buildings that are elegantly ordered, practical without being soullessly utilitarian and pleasing to the eye. Its philosophical foundation stretches back to antiquity, when the Ancient Romans and Ancient Greeks used the simple elegance of mathematical principles to design their palaces, monuments and temples.

Strictly speaking, it is also amusingly misnamed. While the Renaissance Revival is built on a foundation of the original Renaissance principles of the 15th and early 16th centuries, it liberally borrows more ornate elements from the later Gothic and Baroque styles too and a keen observer can spot features from centuries apart sitting side-by-side in the same room. This had the advantage of offering commissioning patrons a generous array of options.

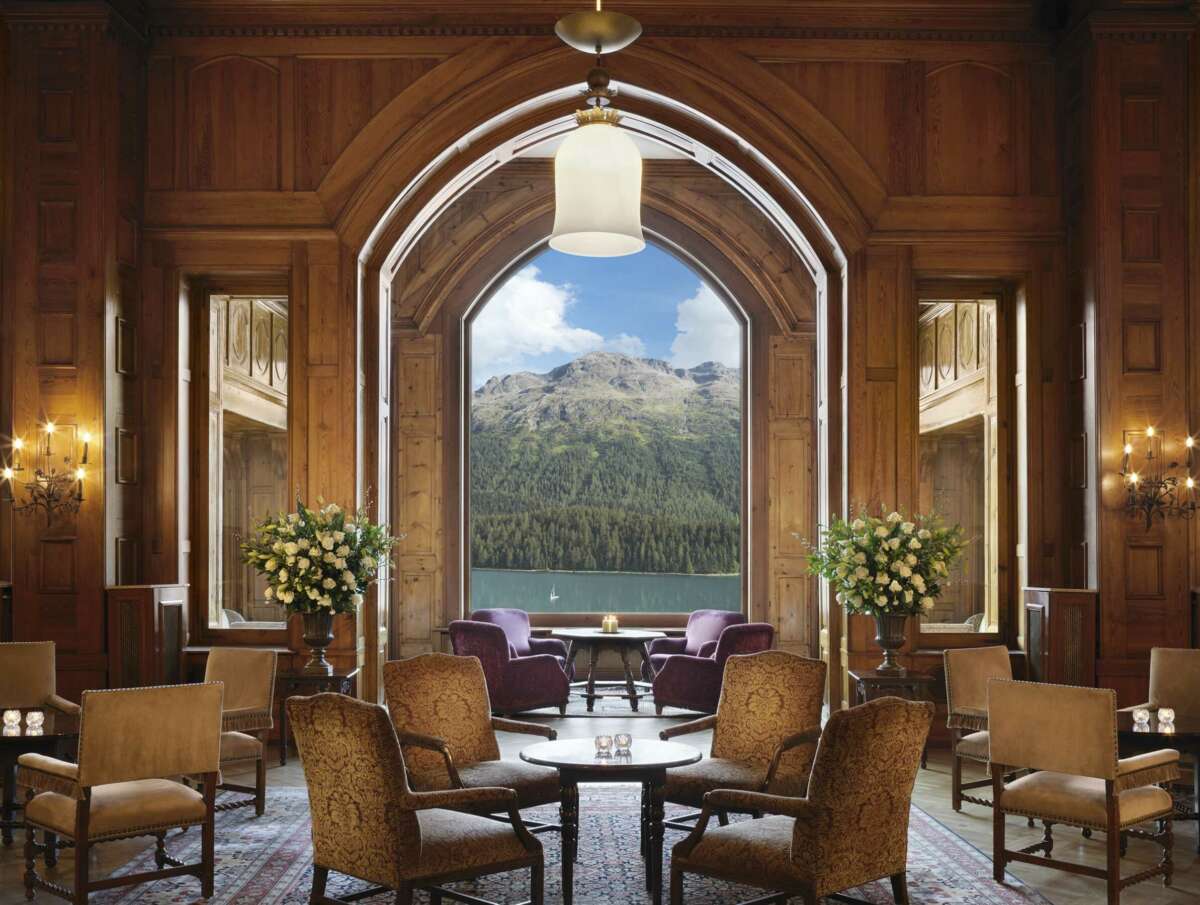

Living room of St. Moritz

One such commissioning patron was Caspar Badrutt. Eager to see the hotel excel, he turned to the Renaissance Revival to help provide an attractive destination for those of refined tastes. Thanks to his decisions, Le Grand Hall is a spacious, well-appointed space that offers grandeur without being overwhelming. The stained-glass windows provide natural light and are reminiscent of those found in churches, while the coffered ceiling recalls the country seats and stately homes of the aristocracy. Meanwhile, the gothic vault and the pilasters of the classical columns at the entrance to the Madonna Room offer more dramatic touches.

Even its walls were carefully designed to impress. Renaissance-era palaces were lined with marble up to chair height to protect them from wear and tear, with tapestries or pictures hung above it, and the Renaissance Revival movement naturally echoed this approach. Genuine marble was expensive, so most hotels of the era used cheaper plaster-based stucco to imitate it instead. However, such was Caspar Badrutt’s commitment that he insisted on nothing but the real thing.

Caspar’s son Hans would continue his father’s work when he took over in 1898 and he went on to pay closer attention to the décor and furnishings. He certainly succeeded in filling Le Grand Hall with a feeling of life and creating an area that combined luxury and refinement with comfort and ease. If the hotel is a theatre that offers its guests a stage, Le Grand Hall is the undisputed main stage where guests can sit and watch the world go by and enjoy conversation over a tea, coffee or an apéritif.

Photographs from the hotel’s archives reveal that Le Grand Hall of a century ago looked much as it does today. The seating areas were spread out across the room, arranged so that guests could sit together comfortably in groups – families, friends, married couples, children with nannies and so on. The armchairs were upholstered with velvet and today’s furniture has been renovated to match the same historical style. On the tables, you can see silver-plated match holders which are used in the bar today. The lights document the transition from floral Art Nouveau to geometric Art Deco, and today they can be found brightening the mezzanine corridors and the Embassy Ballroom.

With its spacious outlook, ornate decor and extravagant architecture, Le Grand Hall continues to captivate as the ‘living room of St. Moritz’. Where else can you find guests from all over the world passing the time over afternoon tea or champagne and caviar?