“Art is the highest form of hope,” wrote Gerhard Richter in 1982. The German painter – now 92 years old and regarded as one of the most important visual artists of the 20th and 21st centuries – has on several occasions compared the process of creating art to an act of faith; a way of going beyond the material world to achieve some form of transcendence. With an oeuvre that straddles the boundary between figuration and abstraction, he has consistently tested both the formal and conceptual limits of painting – a medium to which he has remained committed throughout his career, even during periods when it was out of critical favour.

Richter’s engagement with the potential of art to attain, or at least represent, the sublime, comes to the fore in a fascinating new joint exhibition, Gerhard Richter: Engadin, held across three venues in the Engadin: Hauser & Wirth and the Segantini Museum in St. Moritz, and the Nietzsche-Haus in the Swiss Alpine village of Sils, which the artist first visited in 1989 and regularly returned for summer and winter holidays for more than 25 years.

An ethereal beauty

Awed by the local landscape, Richter returned to the area regularly for summer and winter holidays for more than 25 years, embarking on long hikes during which he would take snapshots of the scenery with his camera. These became the source material for a series of works that illustrate the infinite variety of the natural world: its ethereal beauty, but also its haunting isolation. More than 70 works from museums and private collections, including paintings, overpainted photographs, drawings and objects, are testament to his fascination with the area.

For the curator Dieter Schwarz, an expert on Richter who was responsible for introducing the artist to the Engadin Valley, the exhibition is significant because it charts “the beginning of a new chapter in his landscape painting, which was a counterpart to his abstract paintings”.

Richter took an evident interest in 19th-century German Romanticism, which saw artists elevate nature to a metaphysical status, yet his own work seems less about glorifying the landscape and more about capturing his impressions of its changing state.

A compelling visual experiment

Some of this ambiguity comes from his unique process: on returning to his studio in Cologne after a trip to Switzerland, he would project the photographs he had taken onto canvas and use them as a template for his compositions, which could then be filtered and adjusted to suit his artistic imagination. He would also blur out the wet paint using a soft brush, further distancing the paintings from their real-life origins and giving them an otherworldly feel.

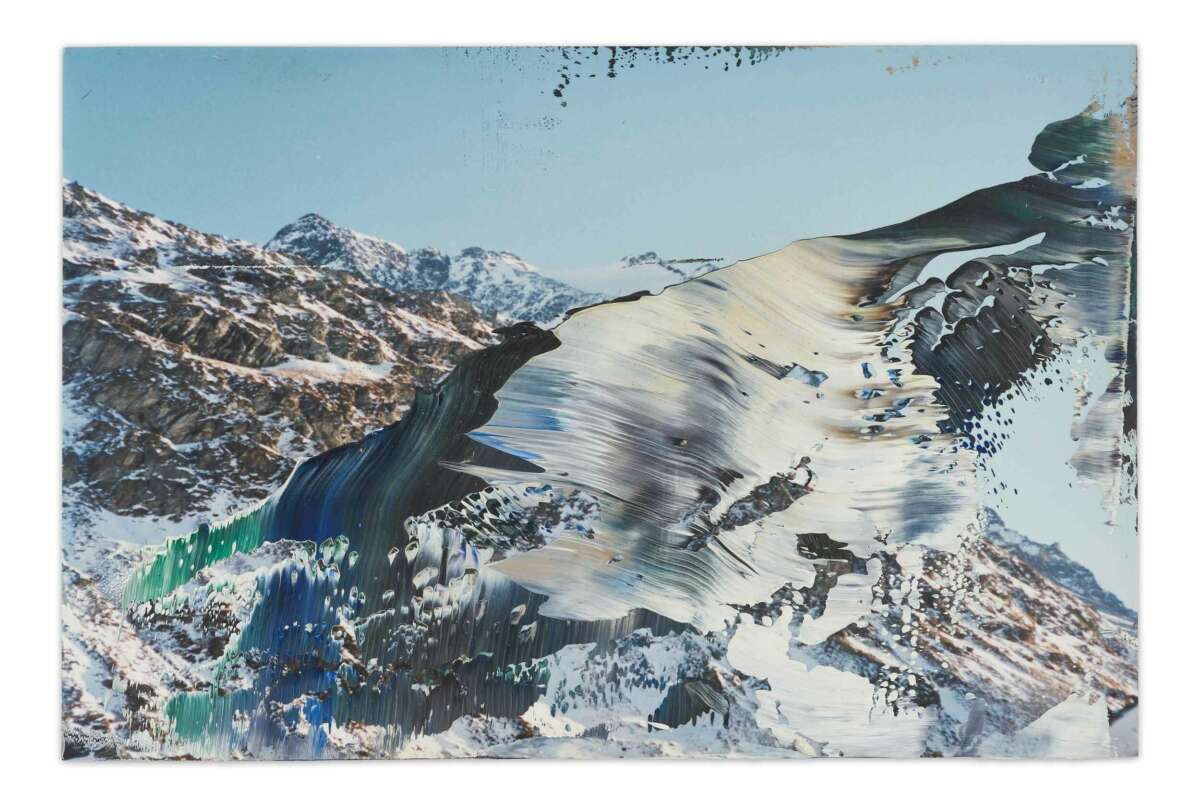

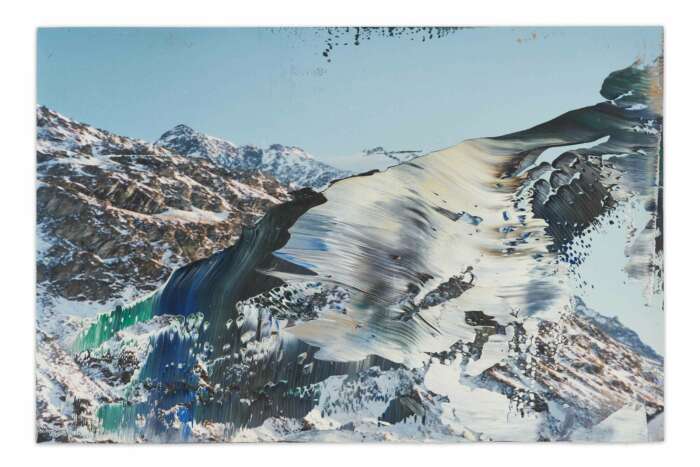

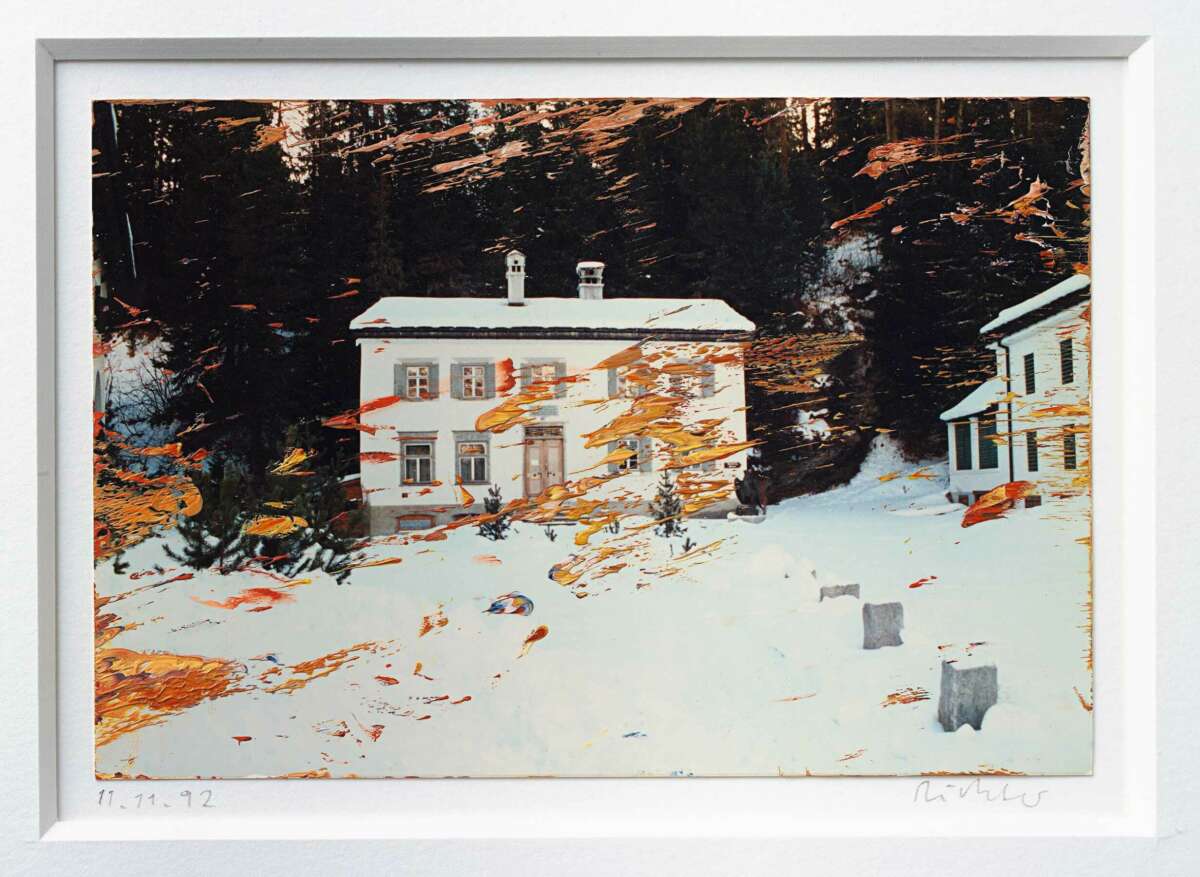

An equally compelling visual experiment comes in the form of Richter’s overpainted photographs, which have their genesis in the ‘colour notes’ he would make on his snapshots using dabs of paint, before realising that the annotated images were interesting in their own right.

In these small but perfectly formed works, more than 50 of which are on display at Hauser & Wirth and the Segantini Museum, landmarks from the Engadin region are transformed into masterpieces of abstraction through the subtle application of oil and lacquer paint, whether representing a smattering of snowflakes on a forest of fir-trees, a mountainside in bloom or the sky bursting into flames.

Though best known as a painter, Richter also produced sculptures in the course of his career (most notably, he designed a monumental stained-glass window for the cathedral in Cologne), and the connecting thread in this tripartite show is in fact a trio of his three-dimensional creations.

In 1992, when exhibiting a selection of his Engadin photographs at Nietzsche-Haus, Richter made an edition of a stainless-steel sphere that reflected the colours and scenery around it. It once again takes pride of place in the museum, with two other orbs from the series appearing in the other exhibition venues. Holding up a mirror to the breathtaking Alpine landscape that surrounds them, they serve as powerful reminders of the influence that the region has had on Richter, as it has on so many other artists over the centuries. If art is indeed the highest form of hope, long may such a place exist to inspire its creation.

Gerhard Richter: Engadin, curated by Dieter Schwarz, is on view at the Nietzsche Haus, Segantini Museum and Hauser & Wirth St. Moritz until 13 April 2024.